It's the final episode of our Life Stages series, and its euphemism-free. We speak to a doctors, lawyers, professors, and funeral professionals about the rules of death; pronouncing, declaring, burying, cremating, willing, trusting, canceling, donating.

Featuring the voices of Dan Cassino, Ken Iserson, Leah Plunkett, Mandy Stafford, and Taelor Johnson.

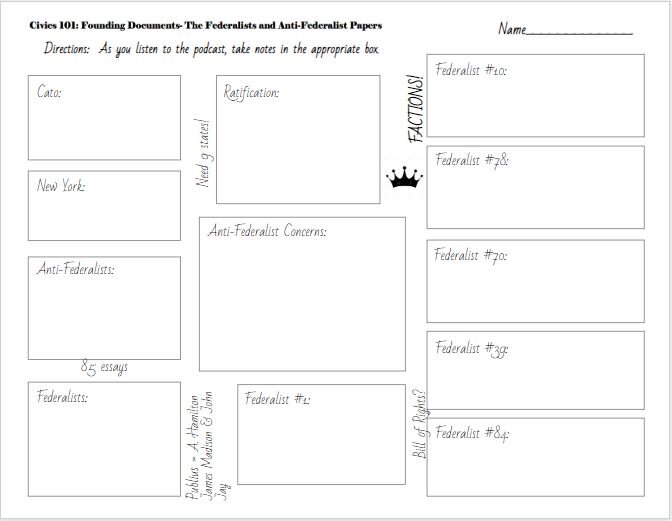

Click here to get a Graphic Organizer for notetaking while listening to the episode.

Episode Segments

TRANSCRIPT

NOTE: This transcript was generated using an automated transcription service, and may contain typographical errors.

Civics 101

Life Stages: Death

[00:00:05] Civics 101 is supported in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Nick Capodice [00:00:05] You know what. More than ever in this series, I am grateful for red tape. Because death is so personal. And in radio we're not supposed to refer to "the listener." But I'm gonna do it. You listener. I have no idea how you want to talk about death. When I was coming up with ideas for the episode I was like I'll open with The Seventh Seal or Bill and Ted's Bogus Journey or Barber's Adagio for Strings. Because I don't know, are you a reverent about death? Does it terrify you? Maybe you're dealing with it right now in your life and it's horrible and it's consuming everything. So all I'll do is say that when I have dealt with death in my own life, I strangely took comfort in the rules and regulations and systems of it. Because I'm sad and I'm angry and I don't know how I'm supposed to feel, but okay let's see what the lawyer has to say. How many copies of the death certificate do we need. Let's talk about the arrangements. But these conversations are so awkward.

Ken Iserson [00:01:06] We don't like to talk about it. We don't like to think about it.

Nick Capodice [00:01:10] This is Dr. Ken Iserson.

Ken Iserson [00:01:14] I'm professor emeritus at the University of Arizona Department of Emergency Medicine.

Nick Capodice [00:01:17] He's written several books on death including Dust to Death: What happens to dead bodies.

Ken Iserson [00:01:21] You know even in the shoot em up cops and robbers and military films and other media where they show lots of deaths and lots of killings, they don't show the funerals. They don't show the dead bodies. Except maybe for Game of Thrones. But in general we don't, a lot of people don't like to go to funerals. That's not part of their life which is kind of strange because of course it is part of life.

Nick Capodice [00:01:52] I'm Nick Capodice.

Hannah McCarthy [00:01:54] I'm Hannah McCarthy.

Nick Capodice [00:01:55] And today on Civics 101 it is the final chapter of our life stages series; Death.

Hannah McCarthy [00:02:01] Can we start with when someone becomes dead.

Nick Capodice [00:02:04] Right, we're not going to get into the sort of philosophical question of when is someone quote dead but we can explore when someone is legally dead.

Ken Iserson [00:02:12] Yeah that's that's a really really big part of the interaction of law and death. Who decides that a person is dead and how is it done. Well in every country in every locale the basic rule is a person is dead when a physician says the person is dead.

Hannah McCarthy [00:02:32] So once they're pronounced dead is that when the death certificate is issued?

Nick Capodice [00:02:37] Yeah and usually someone checks the clock and they step back and they say time of death for 13 or whatever but there are two very different ways you can become dead and Hannah, this can cause some issues regarding what is real.

Dan Cassino [00:02:52] Legal facts and actual facts often but do not always co-exist.

Nick Capodice [00:02:58] You all know that music means there he is making his last appearance in the series, Dan Cassino from Fairleigh Dickinson University.

Dan Cassino [00:03:04] Meaning, the fact that something is legally true does not mean it is actually true. So there's two ways you can be declared dead. So you can be declared dead, declaration of death happens from either a cop or a medic or a judge, or you can be pronounced dead which is by a doctor. Now if you're pronounced dead and a doctor looks at you and says This guy's dead, there's not much disagreement about that and the legal fact of your death and the actual fact of your death are two things that are very much in line. Depending what state you're in between four and seven years if you have disappeared and there is no reason why you've disappeared in the courts are allowed to look into this and decide alright is this person fleeing debt, where they, did they leave a note and say they were going somewhere, if there's no reason why you should be missing and you haven't turned up at your place of business and there's been effort to find you and haven't turned up and they put an ad in the newspaper asking for you to turn up and you haven't turned up guess what. After four to seven years you are legally dead and your heirs can start collect your estate. The government can start giving Social Security to your survivors. Insurance companies have to pay out and if you decide after that you want to come back and you are not actually dead just legally dead, well you're gonna have a hell of a time because the Social Security administration is gonna want all that money back that they paid out to your survivors and they might not want to pay you back. The insurance company while it turns out they cannot actually take the money back from your heirs, it turns out they can sue you if you disappeared on purpose and try and get the money back that they did pay out from you. And so we have all these cases where people who are in fact legally legally dead but not actually that do come back.

Hannah McCarthy [00:04:29] But how often does that actually happen.

Nick Capodice [00:04:31] Dan said there are about 100,000 dead not dead Americans walking around right now.

Hannah McCarthy [00:04:37] That is bonkers.

Nick Capodice [00:04:38] But for the majority of Americans, death will happen in a hospital or home or hospice care and the funeral service will be contacted to assist with what comes next. But Ken told me it wasn't always that way.

Ken Iserson [00:04:52] In the beginning in the beginning of our country families experienced births and deaths at home. They saw many many many little children die at birth. They saw the mothers in large numbers die giving birth or shortly thereafter. They saw what happened to the bodies. They helped bury them they helped prepare them, and then that changed.

Nick Capodice [00:05:22] In fact the antiquated term undertaker which I learned you should never call a funeral professional these days just meant someone who undertook a task. And that person is usually a family friend or relative who helped you bury the body and make arrangements. That person would contact the local cabinet maker to make a coffin and maybe a carriage to take it to the grave site. But that was it. By the way do you know the difference between a coffin and a casket Hannah.

Hannah McCarthy [00:05:48] This isn't a setup for a joke is it.

Nick Capodice [00:05:49] No it's not. No.

Hannah McCarthy [00:05:50] Okay Nick what is the difference between a coffin and a casket.

Nick Capodice [00:05:54] It's the shape. A casket is rectangular and a coffin has that a irregular hexagonal coffin shape.

Hannah McCarthy [00:06:00] That's it?

Nick Capodice [00:06:01] That's it. And as a fun side note, in the 1950s there are about 500 casket manufacturers in the U.S. and today three companies that make 70 percent of the caskets in America.

Hannah McCarthy [00:06:12] So when did Death shift from being the responsibility of families and your local cabinet maker to these funeral professionals.

Ken Iserson [00:06:21] Around and after the Civil War the funeral industry suddenly became a real entity and embalming was developed. And initially it was developed of course for the bodies on the battlefield, especially the officers, they wanted to preserve them and send them home. And then all of a sudden this body arrived that was supposed to be embalmed. And I guess it was to some extent but not in a condition you'd want to look at it. And then the families began using that routinely and gradually sending the whole process over to the funeral director instead of at home.

Nick Capodice [00:07:12] Embalming becomes more popular when formaldehyde becomes readily available in America and embalming fluid sellers would travel the country to give these one day crash courses and how to do it to funeral directors and this means the body can be preserved and therefore more time and consideration given to the funeral service. And that's how we get to today where a funeral director can provide over 130 separate types of services for a family.

Hannah McCarthy [00:07:41] Like what.

Nick Capodice [00:07:42] Set up catered meals for services, they contact the friends and family for you about the death, write and place the obituary, arrange the hearse, the church, gravestone, refrigeration, memorial cards, tent at the gravesite, washing, dressing, cremating casketing, cosmetology and the big one embalming.

Hannah McCarthy [00:08:02] Wow wow. Is it legally required that a body be embalmed nowadays.

Nick Capodice [00:08:05] Absolutely not. But there are laws of it having to embalm or refrigerate or cremate or bury within a certain time window after death. Did you know the U.S. and Canada are the only two countries in the world where enbalming is common and we bury about 800000 gallons of embalming fluid every year. But while all the states have different regulations about burial, embalming is not required as part of your final disposition.

Hannah McCarthy [00:08:31] Final disposition.

Mandy Stafford [00:08:32] A final disposition is that last step.

Nick Capodice [00:08:37] This is Mandy Stafford. She's a funeral director at Mueller memorial in St. Paul Minnesota.

[00:08:41] Hi I'm Scott Mueller president of Mueller memorial and author of the bestselling book What to know before you go.

Nick Capodice [00:08:47] I had the pleasure of speaking with two Mueller Memorial employees Mandy and Taelor Johnson who's in charge of community relations.

Hannah McCarthy [00:08:53] I'm glad that we get to hear from people who actually do this for a living.

Nick Capodice [00:08:56] Right. And the first thing I asked them to do was to help me clear up any misconceptions about the industry.

Taelor Johnson [00:09:03] I'll search sorry but I'll start you right there. Scott doesn't like it when we call it an industry. He prefers to be called a profession.

Hannah McCarthy [00:09:09] Nick you always manage to do this.

Nick Capodice [00:09:12] I know! No. They were very cool about it.

Taelor Johnson [00:09:13] No no no it's a perfect example. Perfect example.

Nick Capodice [00:09:16] If I may say Mandy and Taylor were the exact opposite of that film stereotype of the scary funeral director and they both told me about the laws regarding that final disposition how you end up.

Mandy Stafford [00:09:28] Minnesota has what's called a 72 hour law and so within 72 hours of when someone passes away the family needs to make the decision between having cremation take place being able to do the embalming process or doing what's called a direct burial which means burial takes place without embalming, within the 72 hours.

Hannah McCarthy [00:09:52] Are those your only three options; embalming cremation direct burial.

Nick Capodice [00:09:56] Not even remotely every state may have different laws but in 46 of them you can be buried in your own yard. There are green burials which are alkalis that break your body down, you can be buried at sea. Not to mention the thousands of things you can do with your cremains. And also, and this is where Mandy and Taelor defied my expectations, they expressly said you don't even need a casket or coffin. You need a rigid container if you're cremated. But other than that anything goes. A cardboard box. A bedsheet.

Hannah McCarthy [00:10:26] Wow. Can I ask a quick questino.

Nick Capodice [00:10:28] Yeah go ahead.

Hannah McCarthy [00:10:29] I don't know if you know the answer to this.

Nick Capodice [00:10:29] Sure.

Hannah McCarthy [00:10:30] I had a boyfriend once.

Nick Capodice [00:10:32] Yeah.

Hannah McCarthy [00:10:32] Who. I mean this is this is just a little fantastical but his plan for his death was to be taken out to the forest and and kind of sink into the earth and be taken away by animals. Can you do that can you just let yourself let your dead body be eaten away and taken away just lying out there in the middle of the forest is that legal?

Nick Capodice [00:10:53] That is not legal due to the potential for spreading illness or contaminating a water supply. The body does have to be buried.

Hannah McCarthy [00:11:00] Oh what about a Viking funeral.

Nick Capodice [00:11:04] Like a Pyre?

Hannah McCarthy [00:11:04] Yeah.

Nick Capodice [00:11:05] Like set alight on a boat via a flaming arrow.

Hannah McCarthy [00:11:08] Yeah.

Nick Capodice [00:11:08] You can't do that and you're not the first to ask. That's actually a common question. Cremation has to be done by a licensed crematorium because fires that we set just can't get hot enough.

Hannah McCarthy [00:11:18] How hot exactly did crematoriums need to get to reduce the body to ash.

Nick Capodice [00:11:24] Modern crematoriums get up to about eighteen hundred degrees. There is one and only one outdoor pyre styled crematorium in the US. It's in Colorado.

Hannah McCarthy [00:11:34] Now. Take me through the absolute bare minimum. Someone dies. What do you have to do.

Nick Capodice [00:11:40] If it happened in your home; unless the person was in hospice care, you have to call the police. They will send a medical examiner and determine the cause of death and write the death certificate. But dealing with the body is probably going to cost you. Lots of life insurance plans help you cover those funeral expenses, average burial in America seven to ten thousand dollars, average cremation five to six thousand dollars. If you're working with a funeral home a funeral parlor you'll probably spend at least three thousand dollars.

Hannah McCarthy [00:12:10] But what if you have no money. A relative passes away in your home what can you do.

Nick Capodice [00:12:16] This varies state by state and county by county. But if you're on some manner of governmental assistance that assistance program will negotiate and cover a simple cremation or a burial with the funeral home. Mandy told me it's usually cremation most of the time because the government program will not help pay for a cemetery plot or a headstone. But the real tricky part in this comes not to how it's done but who gets to make that final determination of your final disposition. It's your next of kin. You know about the next of kin order right.

Hannah McCarthy [00:12:46] No I don't.

Nick Capodice [00:12:47] It's like the presidential succession. So first it's your spouse and then it's your children and then it's your parents siblings and grandchildren then grandparents then nieces nephews etc.. Here's funeral director Mandy Stafford again.

Mandy Stafford [00:12:58] So I think that is really the biggest red tape is understanding who has that right to make the decisions and say there are eight children and four of them want cremation and four of them want a traditional casket at service. That's where things can get a little grey so to say. Because here in Minnesota we do need one more than half to sign for cremation to take place.

Taelor Johnson [00:13:27] And if they can't get that majority.

Nick Capodice [00:13:29] Taelor told me that they just get there. They mediate and they discuss it and it almost always gets decided within that 72 hour window.

Hannah McCarthy [00:13:40] So what can I the currently living due to prevent this hassle and debate for my next of kin when the time comes.

Nick Capodice [00:13:48] So you want to make it easier for those you love.

Hannah McCarthy [00:13:50] Yeah.

Nick Capodice [00:13:51] All right. First thing you have to do is fill out an advance directive. I'm going to do it as soon as we record this episode. I swear. You can download the forms for your state. Fill them out in front of a witness. Give a copy to your doctor, to your lawyer, to your parents, to your kids. Keep a note saying you have one in your wallet. That assures your friends and loved ones that what you want to be done with your body will be carried out and no one has to make that grueling decision. But even after you deal with the red tape of the burial, you're not finished.

Taelor Johnson [00:14:22] Yeah there's a lot of things that that we don't think about because there's especially now in the digital age we're living in. People have so many different accounts and and passwords and user names and all that and it's it's hard to figure out exactly how to close out someone's life. You kind of break it down into two different categories, one would be cancellations and one would be more like asset distribution. So if you're looking at cancellations, something like Netflix Netflix doesn't have a contract or anything like that so you can just call Netflix and tell them someone passed away and they'll cancel the account. Because if you are doing that falsely it would be easy for the person to reinstate it. It's not a big deal but you want to use caution when you cancel something like an Amazon account or a an iTunes account because once you do that you lose all of the assets that were being held by that account. So technically speaking when you buy a song air quotes buy a song on iTunes you're actually leasing it for your lifetime.

Hannah McCarthy [00:15:27] Are you kidding me. Like I don't actually own the copy of a League of Their Own that I paid for.

Nick Capodice [00:15:33] Those Rockford peaches are not yours to espy in death Hannah, and my kids can no longer watch all nine seasons of Curious George. Google lets you choose whatever you want to do with your account when it's been inactive a certain amount of time you can let someone else access that or just lock it all shut it down and delete everything. And Facebook lets you assign what's called a legacy contact. Phone companies need to be called appropriately enough but there's one kind of Web site that is very persnickety about death.

Taelor Johnson [00:16:05] So. So if you have like an online stock account through E-Trade or T.D. Ameritrade or something like that you would you would want to make sure that beforehand, and this is a huge takeaway and if I could if I could like shake people and say do this it would be it would be to say go into, if you have these kinds of accounts if you have a brokerage account which is just an account that has that you can trade stocks in or something to that effect. Make sure you have a transfer on death filled out because you are not required to fill that out when you when you open a brokerage account. You are required to fill out a beneficiary for an IRA but if you've got an online brokerage account you have to go in specifically and fill out a transfer on death form. And a big thing there is is the biggest most important thing in either of those cases is to not ever make any transactions after someone has died. If you have the username and password for your spouse or your sibling or something like that if you're there the executor of their state whatever it doesn't matter do not go and make changes because the IRS will not look fondly upon a discrepancy between transactions that were made by quote someone you know like it by a living person and that conflicting with a a certain death certificate.

Hannah McCarthy [00:17:35] Okay so now we're into an area that is famously touchy right. Leaving your assets after death your will.

Nick Capodice [00:17:44] Right. Did I ever tell you that I had a program on my Apple iic when I was a kid called Will Writer. My sister and I wanted to start a will writing business.

Hannah McCarthy [00:17:52] Why were you... as children?

[00:17:56] Can you write your own will. Sure you can.

Nick Capodice [00:17:58] There are a ton of YouTube videos with will advice out there by the way.

[00:18:01] You can also build your own house but that doesn't mean you should. A will is an important legal document.

Hannah McCarthy [00:18:08] When you're left something in a will, does the government take some of that is it taxed?

Nick Capodice [00:18:13] This is called an estate tax and the federal government won't do it unless it is eleven point eight million dollars or more that you're left. The state though can levy state taxes on that gift at a lower level but it's still around the million dollar range. However be ye warned about capital gains tax. So that's like if you're left a house that's worth 250 grand and you sell it for 275. You get taxed on that twenty five thousand dollar difference.

Hannah McCarthy [00:18:43] Why are wills so complex.

[00:18:44] I know, right? So I asked Leah Plunkett from University of New Hampshire School of Law, why can't I just write on a piece of paper I leave everything to my wife and kids and they know what's best. Why are they so tricky.

Leah Plunkett [00:18:55] Wills are complicated because we need to make sure that they are made with an understanding by the person who's making them of what they're doing that they're not being coerced or controlled but they're being made knowingly and voluntarily and of free will. It's so crucial that we know that that's really your decision. So I've got a piece of paper in my blue professor pen you know on the desk right here. If I just write I leave everything to my husband two kids and a dog they know what's best, you're an appropriate witness because you're not related to me, you don't have a stake in my will. But how the heck is you know a court or the bank that has the mortgage on our house or any of these other official entities supposed to be able to know that this piece of scrap paper that I scribbled on was really me, that I was really doing it of my own free will. If there aren't certain, I sometimes tell my law students that going to law school is like going to Hogwarts that there's certain phrases and certain words that are legal terms of art. And if you use them the right way then magic happens. And it's not flying or unforgivable curses but you do have the power to alter the outcome of someone's life or an institution's trajectory.

Hannah McCarthy [00:20:18] These are phrases like I Hannah McCarthy being of sound mind and body.

Nick Capodice [00:20:22] Yeah. Terms like bequest, devise, right of representation, executor, the female version of which was once an executrix by the way. An executor is the person who carries out the will and with very few exceptions your will is going to go through probate, which is a court review to prove the validity of the will. Probate comes from Latin for to prove. And that process of probate can take months up to years.

Hannah McCarthy [00:20:47] And there's no way around this.

Nick Capodice [00:20:49] There is a way and I feel like I'm in a commercial when I'm talking about this stuff but it's creating a trust instead of using a will to give stuff to someone else. If you create a trust you can choose possessions and money to give to someone before you die, and when you die, and after you die. And trusts do not go through probate, they don't go through court.

Hannah McCarthy [00:21:12] OK I. I knew a good number of people in college who actually had trusts that like they wouldn't be able to access them until they were like 21 or 25 or 30 but some of these trusts, tell me if this is an actual legal thing, had stipulations like you have to have graduated from college or you can't get in trouble with the law.

Nick Capodice [00:21:35] You can put conditions like that on any gift, will, or trust. State supreme courts have actually ruled on this. As long as the conditions don't break the law they are binding and you have to do the thing to get that money. Even things like you have to have an Ivy League diploma or you cannot marry outside the faith.

Hannah McCarthy [00:21:55] Wow that's really kind of restrictive and manipulative.

Nick Capodice [00:21:58] But it's legal, man. It's the law.

Hannah McCarthy [00:22:01] Can I just ask you Nick, after all of this, have you decided on your final disposition?

Nick Capodice [00:22:10] I haven't yet but there is something that Ken Iserson from University of Arizona said to me that opened up a possibility I hadn't even considered.

[00:22:22] There there's so much suffering in creation as we know it. We remember today those made a difference in the relieving that suffering by generosity.

Ken Iserson [00:22:34] I always have felt that people who donate their whole body to science are really benefactors for humanity.

Nick Capodice [00:22:45] If you contact your local medical school and you start the process which also requires signing forms in front of witnesses, you can leave your body to medical science. Once it's been used it's been studied and it's been dissected it's cremated and the criminals are sent back to you usually for free.

Ken Iserson [00:23:01] You know there's one other thing that's associated with it. I think it started at the University of Arizona Medical School and has gone to other places since. But the medical students actually have a service for all the people who donated their bodies for their anatomical training. And it's rather moving the whole class gets together and it's led by a diverse religious people.

[00:23:30] I never knew where you were from. I never knew your face, never knew your voice. I committed every twist and turn of each and every vein and artery to memory.

Nick Capodice [00:23:44] Even though the way we think about death has changed so much in America has Taelor who deals with death every day if she had any advice for the rest of us.

Taelor Johnson [00:23:53] Definitely don't shield your children from from death, don't shield anyone from it. Because we're we're pretty well distanced now as a society from death. We have someone who comes to our house and and takes the body away and there are, we don't have to be close, closely involved as as even two generations before us were. So I just encourage people because I spend a lot of time working on grief and those those few days that that acute loss period is really so vital framing how your grief experience is gonna go for the rest of your life. So so don't back away from it, kind of lean into the the rites and ceremonies that happen when someone dies and always go to the funeral.

Nick Capodice [00:24:41] Mandy told me that it helps with the grieving process. And she told me a story about the one time she didn't go to a colleague's and how she still doesn't have closure in that death. Ken told me that it's great maybe even preferable to not have a funeral at all but have a memorial service like months or weeks after to celebrate the life of that person.

Hannah McCarthy [00:25:01] I have to make an advance directive. Write a will. Write down passwords and tell my next of kin not to cancel my Amazon.

Nick Capodice [00:25:10] Right.

Hannah McCarthy [00:25:11] I have a lot of tasks to do before I die.

Nick Capodice [00:25:14] May it be a long time my friend.

Hannah McCarthy [00:25:18] So that's it. I think we're done. Cradle to grave.

[00:25:22] Yeah. Almost. Just one last word to kind of put the hat on the snowman. Before I said goodbye to Dan, he said he wanted to put in one final salvo, a defense for these things that you and I consider onerous.

Dan Cassino [00:25:37] All of these things we're talking about are about bureaucracy or about the federal government and putting red tape in your way. And we hate bureaucracy. We hate that red tape. But turns out this is actually a really good thing. So think about it. If I go to the DMV and a person in front, that person handing me a ticket tells you a line to get in. If Bill Gates goes to the DMV he goes the front that person gives him the same ticket. Lets say that person really loves Bill Gates loves Windows. I'm sure that person exists. They go out they say we want to help Bill Gates, what can they do? Nothing. They give him the same ticket. They are constrained. They have really no way of doing anything other than the one thing they're allowed to do. The whole idea of bureaucracy is it's small d democratic. Everyone gets treated in the exact same way because the bureaucrats don't have any discretion, they have no ability to treat people differently so you and me and Bill Gates and the person's mother in law and everybody gets treated the exact same way when they show up. So bureaucracy, while we hate, it while it's terrible because no one has discretion they can't help you out or something goes wrong, guess what. It's the most democratic part of our government.

Nick Capodice [00:26:37] So here's to bureaucracy a word that I can just never spell.

Hannah McCarthy [00:26:40] Me neither

Nick Capodice [00:26:41] Really?? You also have that one?

Hannah McCarthy [00:26:42] I can never.

Nick Capodice [00:26:43] It kills me that red squiggle. I'm like "Today I'm not going to get the red squiggle" and there it is.

Hannah McCarthy [00:26:49] Nick it was fun exploring the life of an American with you.

Nick Capodice [00:26:55] The pleasure was more than half mine. I agree, Hannah. That'll do it for this episode and this series. Today's episode was produced by me Nick Capodice with you Hannah McCarthy. Thank you.

Hannah McCarthy [00:27:02] Oh you're welcome. Our staff includes Jacqui Helbert, Daniela Vidal-Allee and Ben Henry. Erika Janik is our executive producer and owns a non digital copy of a League of Their Own.

Nick Capodice [00:27:13] Maureen McMurray rides A Pale Horse.

Hannah McCarthy [00:27:15] Music in this episode by elephant funeral Blue Dot sessions Seb Wildwood coconut monkey rocket and Chris Zabriske. Scott Grant and did this inspirational song you listen to here.

[00:27:25] Don't you just want to walk forcefully up a mountain and stand there with your hands on your hips. Civics 101 is a production of a NHPR New Hampshire Public Radio and is supported in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.