When a monarch dies, power stays in the family. But what about a president? It was a tricky question that the founders left mostly to Congress to figure out later. Lana Ulrich, of the National Constitution Center, and Linda Monk, constitutional scholar and author of The Bill of Rights: A User's Guide, explain the informal rules that long governed the transition of presidential power, and the 25th Amendment, which currently outlines what should happen if a sitting president dies, resigns, or becomes unable to carry out their duties.

Click here for more charts of Civics 101 episodes by Periodic Presidents!

TRANSCRIPT

Nick Capodice: [00:00:00] Hannah we have made a lot of episodes of Civics 101 since the show started in 2017. And at any one time we've got a list of 20 to 30 different topics that were either already working on or want to do soon. And yet there are few topics we keep coming back to over and over.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:00:21] Yeah, I mean, elections and voting, those are two I can think of. Yeah, we could probably fill a dozen episodes with things about the election process, the politics of voting, of representation.

Nick Capodice: [00:00:33] Yeah, there's one topic we've talked about multiple times on the show because it keeps coming up in the news during the presidencies of both Donald Trump and Joe Biden.

News Clip: [00:00:41] Have you emailed any members.With the investigative.Branch about.The President's health or the president's decline?Do you believe he's capacitated? Well, I think that we have got to be very careful. He needs to start.

Nick Capodice: [00:00:54] It has to do with presidential power and checks on that power.

News Clip: [00:00:58] The fish stinks from the head. Plain and simple. And so I believe the president is dangerous and should not hold office one day longer.

Nick Capodice: [00:01:09] But it's not impeachment. It has to do with the responsibility of the president, the vice president, and the cabinet to ensure we have a leader who is able to do their job.

News Clip: [00:01:20] I'm not saying he's not a danger. I do believe that there's grave risk there. But we've got 13 days.

Nick Capodice: [00:01:27] We're talking about the 25th Amendment.

News Clip: [00:01:30] People inside the.Administration, people in the cabinet were whispering about invoking the 25th Amendment. It's staggering. We're not at a 25th Amendment level yet.

Nick Capodice: [00:01:47] This is Civics 101. I'm Nick Capodice.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:01:49] I'm Hannah McCarthy.

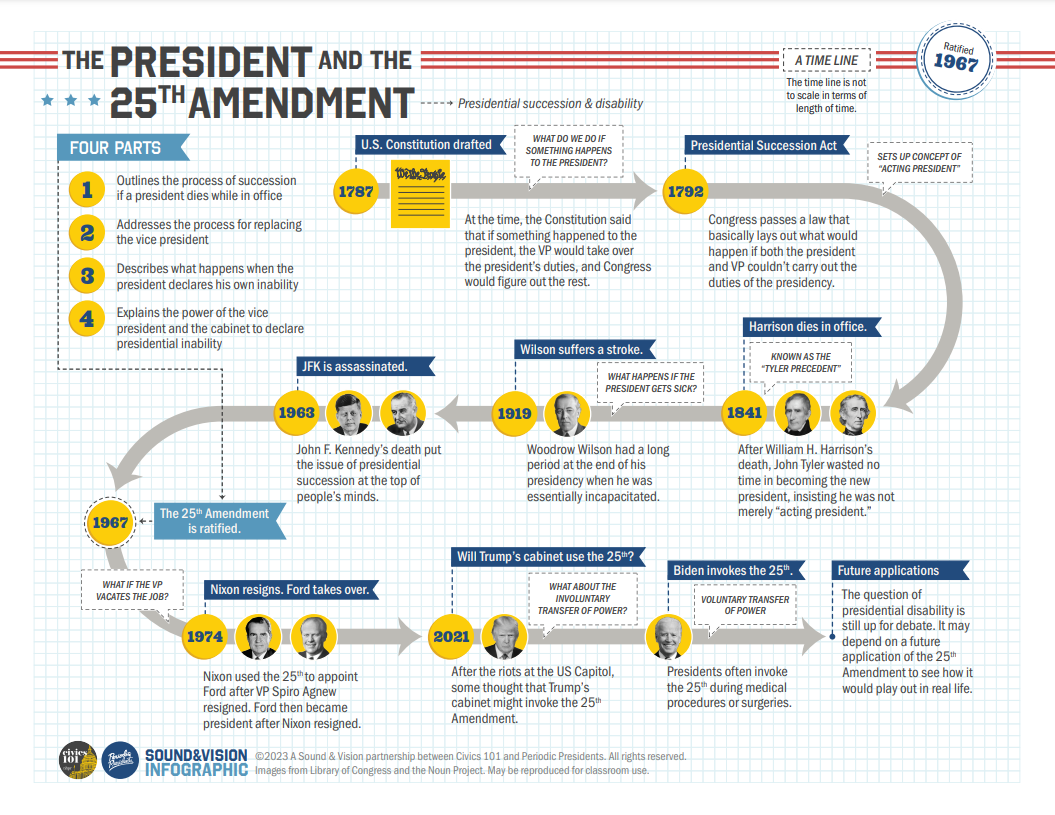

Nick Capodice: [00:01:50] And today we are going to break down the 25th Amendment. This is the amendment that lays out what happens when, for whatever reason, the president cannot perform the duties of that office. And there are four parts to this amendment. The first part deals with the line of succession. The second is about replacing the vice president. The third is about when the president declares their own inability. And the fourth, the most debated, is about the vice president and cabinet's power to declare presidential inability. So today, we're going to explore what this 25th Amendment thing is all about anyway, and why Part four especially, is not as straightforward as it seems.

Nick Capodice: [00:02:28] And to do that, we need to go back to the beginning, to the creation of the Constitution, because there was a lot of time between then and when the 25th Amendment was actually ratified in 1967, the year was 1787, a bunch of men and Whigs were crowded in a room in Philadelphia debating how our government should work. And as it is often said, it was hot. Very odd. We're talking about the Constitutional Convention. And one subject of debate was what do we do if something happens to the president?

Lana Ulrich: [00:03:11] Well, they were debating exactly how they should frame the language addressing presidential succession in the Constitution. And they went back and forth as to how to say, you know, what happens when the president becomes disabled? Should there be an election? Should there not be an election?

Nick Capodice: [00:03:27] This is Lana Ulrich. She's the vice president of content and senior counsel at the National Constitution Center.

Lana Ulrich: [00:03:34] So they finally settled on the language that is included in the original Constitution and Article two, Section one, clause six, which says in case of the removal of the president from office or of his death, resignation or inability to discharge the powers and duties of the set office, the same shall devolve on the Vice President and the Congress may by law provide for the case of removal, death, resignation or inability, both of the President and the Vice President declaring what officer shall then act as president and such office shall act accordingly until the disability be removed or a president shall be elected. And that seemed to clarify a bit as to what would happen, but it didn't answer all of the questions. And there was one delegate in particular, Dickinson, who was taking notes during the debate and sort of wrote to himself, what is the extent of the term disability and who is to be judge of it?

Nick Capodice: [00:04:29] John Dickinson, who represented Delaware at the Constitutional Convention, was a supporter of the Great Compromise. This is what gave smaller states equal representation to larger ones in the Senate and proportional representation in the House. And that word disability is very, very complicated. Throughout U.S. history, there have been deeply ingrained societal prejudices and discrimination towards people who have disabilities or require accommodations. So that word carries a lot of weight.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:05:00] So basically, the only real things the Constitution said at the time were that if something happened to the president, the vice president would take over the president's duties and that Congress was in charge of figuring everything else out, correct? Yeah.

Nick Capodice: [00:05:17] The Constitution left Congress to iron out many of the logistics of presidential succession, but it also failed to answer the question what does it mean for the president to be unable to carry out their duties? And perhaps even more importantly, who determines that the first piece of legislation that Congress passed that clarified the logistics of succession was the Presidential Succession Act of 1792, which basically laid out what would happen if both the president and vice president were unable to carry out the duties of the presidency.

Lana Ulrich: [00:05:50] And so something that is debated to this day. Now, what laws did Congress pass to help build on what was laid out in the Constitution?

Nick Capodice: [00:06:02] The first thing Congress did pertaining to that was to pass the Presidential Succession Act of 1792, which basically laid out what would happen if both the president and vice president were unable to carry out the duties of the presidency.

Lana Ulrich: [00:06:16] Under the first Presidential Succession Act. It was the president pro tempore of the Senate and then followed by the Speaker of the House.

Nick Capodice: [00:06:23] But at the time, the law still stated that whomever replaced the president would serve as, quote, acting president until the next election.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:06:32] What is the difference between acting president and just president?

Nick Capodice: [00:06:37] That's the thing. The word acting suggested that there was some distinction between the two, but those distinctions weren't actually written out. And then John Tyler came along. And as so often happens, when you put a rule into practice for the first time, you realize that your interpretation is not the only interpretation.

Lana Ulrich: [00:06:57] Right. So William Henry Harrison was the first president to die in office, and he died on April 4th, 1841. His vice president, John Tyler, basically just insisted that he became president of the United States and was not merely acting president.

Nick Capodice: [00:07:12] Right off the bat, John Tyler seemed pretty eager to move into the White House and disregard the cabinet that his predecessor had appointed. And he told the cabinet, quote, I shall be pleased to avail myself of your counsel and advice, but I can never consent to being dictated to as to what I shall or shall not do. I, as President, will be responsible for my administration. And then he basically said that if they didn't agree with that, they were welcome to resign. And some people felt that this was a misinterpretation of what it means to be an acting president.

Lana Ulrich: [00:07:46] This became known as the quote unquote, Tyler precedent. And it was pretty controversial. And not everyone agreed that the vice president automatically became president, even if the president died in office. Even former President John Quincy Adams wrote to himself, I paid a visit this morning to Mr. Tyler, who styled himself president of the United States and not vice president, acting as president, which should be the correct style.

Nick Capodice: [00:08:10] Former President Harrison's cabinet had understood that the president would only do things if the majority of his cabinet approved of them, and they expected Tyler to follow the same rule as acting president, that he would consult them, trust their judgment, and wouldn't make decisions unless they approved.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:08:26] But this wasn't Tyler's cabinet, right? These were people appointed by Harrison.

Nick Capodice: [00:08:31] Yeah, they weren't his people. And to be frank, there was no love lost there.

Lana Ulrich: [00:08:35] Yeah. I mean, I think there were some that may have agreed with his interpretation, but as you know, John Quincy Adams did not. But Tyler basically took the oath of office. He gave an inaugural speech and he moved into the White House. And so there just to quell any doubts that he was, in fact, president, they were they were silenced at that time.

Nick Capodice: [00:08:55] And this is how we end up with the Tyler precedent, where the line between president and acting president is pretty much nonexistent.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:09:05] What about those times when the president is not obviously permanently out of office either because they've died or resigned? What if the president gets sick or has an ongoing medical issue?

Lana Ulrich: [00:09:19] There were sort of unspoken norms about what would happen if, at the same time if a president became disabled. And throughout history there were many presidents who were quietly incapacitated and due to many reasons, including the fact that there was no constitutional mechanism in place, they just kind of worked quietly behind the scenes to keep his illness under wraps until the next election. I mean, this happened with Woodrow Wilson, had a severe stroke and for a long period of time toward the end of his term, he was essentially not acting as president. But basically his wife and his cabinet were just kind of acting in his stead. Yeah.

Nick Capodice: [00:09:53] And this informal behind closed doors method of the vice president, the cabinet, even the president's spouse was working well enough, even though Congress wasn't really privy to it and didn't have much power over it. There wasn't enough urgency in Congress to rally behind something like a constitutional amendment until the threat of nuclear war came along.

Lana Ulrich: [00:10:17] Right around the time of President Eisenhower, who was also ill.

News Clip: [00:10:21] Stricken with ileitis, an inflammation of the lower intestine. The 65 year old chief executive was taken from the White House.

Lana Ulrich: [00:10:27] Which coincided with the Cold War.

News Clip: [00:10:29] Soviet Unionn Has informed us That over recent years It has devoted extensive resources to atomic weapons.

Lana Ulrich: [00:10:38] It became clear that we needed something that was a bit more formalized.

Nick Capodice: [00:10:42] Nothing really happened immediately, though. There was a proposed amendment in 1963 that would give Congress the power to determine if the president was unable to discharge their duties. But many argue that it gave Congress too much power, especially considering that Congress already had the power of impeachment.

Lana Ulrich: [00:10:59] And I think the crucial moment in time was after President John F Kennedy was assassinated.

News Clip: [00:11:05] From Dallas, Texas. The flash apparently official. President Kennedy died at 1 p.m. Central Standard Time, 2:00 Eastern Standard Time, some 38 minutes ago. Vice President Lyndon Johnson has left the hospital in Dallas, but we do not know to where he has proceeded. Presumably, he will be taking the oath of office shortly and become the 36th president of the United States.

Linda Monk: [00:11:41] And then Lyndon Johnson was in office without a vice president and he had a history of heart attacks.

Nick Capodice: [00:11:48] This is Linda Monk, constitutional scholar and dear friend of the podcast and author of The Bill of Rights A User's Guide. We have finally reached the 25th Amendment, which gives clearer rules about what to do if the president cannot carry out their duties.

Linda Monk: [00:12:03] So that's when Congress in 65 finally passed it through Congress, and then it was ratified, I believe, in 67.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:12:11] So this amendment does not come up until after we have had several presidents die or have major illnesses while in office.

Nick Capodice: [00:12:20] Yeah, And John F Kennedy's death, which made Lyndon Johnson president, put the issue of succession at the top of people's minds. The amendment was ratified in 1967. Here is Lana Ulrich again.

Lana Ulrich: [00:12:33] And so when President Nixon resigned in 1974, Vice President Ford became president under Section one.

News Clip: [00:12:40] To continue to fight through the months ahead for my personal vindication. Would almost totally absorb the time and attention of both the president and the Congress in a period when our entire focus should be on the great issues of peace abroad and prosperity without inflation at home. Therefore, I shall resign the presidency effective at noon tomorrow. Vice President Ford will be sworn in as president at that hour in this office.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:13:19] But what if the vice president vacates the job? Because in that example, Gerald Ford was not Nixon's original vice president. He became vice president after Spiro Agnew resigned.

Nick Capodice: [00:13:42] Well, that's part two of the 25th Amendment.

Lana Ulrich: [00:13:44] So this requires the president to nominate a vice president when the office is vacant, subject to the confirmation by a majority of the House and the Senate.

News Clip: [00:13:55] Mr. Nixon has asked the Republican hierarchy to propose possible successors by tomorrow evening. His choice and many names are being mentioned tonight, will have to be approved by majority vote of each House of Congress.

Lana Ulrich: [00:14:08] So in 1973, Gerald Ford became vice president through Section two. After Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned. And then when Ford took over the presidency the next year, he invoked Section two and nominated Nelson Rockefeller to fill his vice presidential vacancy.

Nick Capodice: [00:14:26] And now we're going to get into those circumstances where the president hasn't died, but for some other reason, they are unable to do the job, either temporarily or permanently. And this is section three. Section three is about the president's responsibility to decide and disclose when they need to give their duties to the vice president. This is known as a voluntary transfer of power.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:14:49] So if the president needed a colonoscopy, for example.

Nick Capodice: [00:14:52] Exactly. Actually, most examples of this happening have to do with colonoscopies, specifically. For example, President George W Bush invoked Section three when he had to undergo colonoscopy, putting Vice President Dick Cheney temporarily in charge.

Lana Ulrich: [00:15:07] In 1985, President Ronald Reagan was also about to undergo colon cancer surgery. And so he designated Vice President George H.W. Bush to be acting president.

Nick Capodice: [00:15:18] And recently, President Biden discharged his duties to Vice President Kamala Harris.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:15:22] Because of a colonoscopy.

Nick Capodice: [00:15:24] Because of a colonoscopy.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:15:29] And this is the responsibility of the president, right? They have to be the one who says, okay, I'm going to transfer power right now.

Lana Ulrich: [00:15:35] You one would assume so. Yes. Since it's since it requires a written declaration to both transfer the power and then to resume power after the president's disability is removed. Yes.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:15:46] Isn't that interesting the way that Lana says one would assume so. I think the implication there being, as with so many wishy washy interpretations of the Constitution or.

Nick Capodice: [00:15:59] Flat out disregard of it.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:16:00] Disregard for the Constitution, the idea is, you know, this is how it has happened and might happen in the future, but anything can be done differently. And sometimes we do things differently and that can cause a constitutional crisis. So this is all voluntary.

Nick Capodice: [00:16:18] Yeah. And this is called a declaration of inability, where the president submits a notice to Congress saying presidential power is being discharged to this person, either permanently or until such and such a time. And if the president submits that, they then submit a follow up declaration when they are able to retake their duties. And this has been used, as we said, several times by different presidents.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:16:42] What about an involuntary transfer of power? Is it possible for a sitting president to be removed involuntarily without an impeachment?

Nick Capodice: [00:16:51] This brings us to the quite complicated part four of the 25th Amendment, and we're going to talk about that right after this break.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:17:00] But before we go, I have a feeling you're listening to this podcast because you want to know more about American democracy, but we don't tell you everything on the podcast. We sure don't. A lot of it gets cut in actual fact, sometimes the very best parts. But we have a place to put that. It's called Extra Credit. It's our newsletter and you could subscribe to it at our website, civics101podcast.org.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:17:26] We're back. This is civics one on one. And we are talking about what happens when the president dies, resigns, or decides they need to temporarily hand over their presidential duties to the vice president for a medical procedure or something like that. But those processes are not the reason why. About two years ago, in the beginning of 2021, everyone was suddenly talking about the 25th Amendment in terms of the vice president or the president's own cabinet taking away the president's power. Specifically, I'm talking about a lot of people wondering whether former President Donald Trump's vice president and cabinet might declare that he was incapable of doing his job, which of course, did not happen.

News Clip: [00:18:08] But in the immediate aftermath of January 6th, members of the president's family, White House staff and others tried to step in to stabilize the situation, quote, to land the plane before the presidential transition on January 20th. You will hear about members of the Trump cabinet discussing the possibility of invoking the 25th Amendment and replacing the president of the United States.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:18:36] So what does the 25th Amendment say about those situations where the removal of power might not be voluntary?

Lana Ulrich: [00:18:48] Yeah. So section three is the voluntary transfer of power. But Section four details what happens when there may need to be an involuntary transfer of power when the president, for it's assumed medical reasons, is unable to make that conscious decision, whether he's in a coma or whether he has maybe a very severe mental impairment progressed dementia. In that situation, it allows for the vice president to be the crucial decider, essentially, and working with either the heads of the cabinets, the heads of the departments and or a disability review body that Congress may establish to determine that the president is no longer able to fulfill his duties and therefore trigger Section four and the mechanisms by which to involuntarily take power away from the president.

Nick Capodice: [00:19:40] That is Lana Ulrich, again, of the National Constitution Center. And this is Linda Monk, again, constitutional scholar and author of the Bill of Rights A User's Guide.

Linda Monk: [00:19:48] We talk about disability as though it's physical disability, but I think what the controversy about President Trump is raising is whether or not the president is capable of caring. Now, maybe that's not a physical disability, maybe that's other kinds of capabilities.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:20:09] So who gets to make that call?

Lana Ulrich: [00:20:10] Yeah, under Section four, the vice president is really the the one who starts the process to determine that the president is is disabled. And then if the president has the opportunity to contest that, but then the vice president and the department heads can go back to Congress and contest the president's contesting essentially as well. And so and if they're successful, then the vice president becomes acting president.

Linda Monk: [00:20:35] The language is, is that a majority of the cabinet and the vice president have to be involved. If it starts within the executive branch, if the president doesn't go along, it goes to Congress anyway. And it has to be a two thirds vote. That's a pretty big vote.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:20:56] So this is not something the vice president or the cabinet can do without the approval of Congress.

Lana Ulrich: [00:21:02] You know, we have impeachment, and that's a political process for removing the president. And I think that the 25th Amendment contemplates some kind of of disability other than, you know, the president is, you know, maybe did something illegal, is is just not performing well. There's got to be something else there. But it's it's not ultimately up to, say, the White House doctor to make that decision. I think the vice president may certainly consult with the president's doctors and ask for an opinion. But ultimately, I think it does boil down to a political decision to actually take that step, to say, okay, we're going to invoke Section four of the 25th Amendment.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:21:42] Has that ever happened?

Lana Ulrich: [00:21:43] No, it hasn't. And it's controversial for many reasons. One being that it takes power away from a duly elected president, essentially, but the other is that it's never been invoked. So we don't really know how the procedure and the practice will play out. And there are a number of gaps that are still left open. So there's a lot of open questions under this mechanism.

Nick Capodice: [00:22:04] For example, during Ronald Reagan's presidency, some of his aides suspected he had developed symptoms of Alzheimer's that were compromising his ability to do the job.

Lana Ulrich: [00:22:14] Some of his aides had discussed that among themselves, I think especially after Iran-Contra happened.

News Clip: [00:22:20] Good evening. I know you've been reading, seeing and hearing a lot of stories the past several days attributed to Danish sailors, unnamed observers at Italian ports and Spanish harbors and especially unnamed government officials of my administration. Well, now you're going to hear the facts from a White House source and you know my name.

Lana Ulrich: [00:22:40] And they briefly discussed it. And then I think they decided to do a case study and they went the next day and spoke with with the president and sort of interviewed him. And then they decided, well, he was acting completely normal. And so they felt that it wasn't appropriate at that time to invoke Section four. But they but they had kicked the idea around.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:22:59] Why would members of the executive branch, like the vice president or the Cabinet, choose to invoke the 25th Amendment instead of handing over things to Congress for impeachment?

Lana Ulrich: [00:23:10] You know, we have impeachment. And that's a political process for removing the president. And I think that the 25th Amendment contemplates some kind of of disability other than, you know, the president is, you know, maybe did something illegal, is is just not performing well. There's got to be something else there.

Linda Monk: [00:23:28] You know, our framers were very good at putting stumbling blocks to the exercise of power. And the reason you'd want to start with any kind of removal from office, from within the executive branch is because those people are supposed to be at least by constitutional duty, most. Oil to the president. This must be a blow to the Constitution and the country first. But they wouldn't have gotten there without the president. So you think those would be the people who would be most capable of making that determination without political motivation?

Nick Capodice: [00:24:03] For example, in 2021, some members of Congress and the public called on Vice President Mike Pence to invoke the 25th Amendment because of President Donald Trump's potential responsibility in and handling of the January 6th riot on the Capitol during the certification of the election.

News Clip: [00:24:21] He may have only 13 days left as president, but yesterday demonstrated that each and every one of those days is a threat to democracy. So long as he is in power. The quickest and most effective way to remove this president from office would be for the vice president to immediately invoke the 25th Amendment.

Linda Monk: [00:24:46] Either way, it's going to come back to Congress. It's going to come back to the leadership in Congress and the vice president.

Nick Capodice: [00:24:54] But at the end of the day, that question that John Dickinson scrawled in his notes back in 1776 at the Constitutional Convention, what is the extent of disability and who is to be the judge of it is still up for debate.

Lana Ulrich: [00:25:10] Yes, it's definitely still an open question. And I think it's going to depend on maybe, you know, obviously a future situation that would call for the application of the amendment to see how it kind of plays out in real life.

Linda Monk: [00:25:23] Again, this is where I think Alexis de Tocqueville said it never ceases to amaze him how wonderful the Americans were at ignoring and avoiding the contradictions of their constitution. So oftentimes in our constitutional interpretation, it's what the political actors choose to do. And that that is part of the Constitution. It's not just supposed to be automatic words on paper. It's people exercising their judgment.