Today we’re exploring the relatively recent phenomenon of Presidential Debates. How are they run? When did we start doing them? Why was George HW Bush looking at his watch?? And most importantly, why should we keep doing them?

Our experts in this episode are debate scholar Alan Schroeder, and Executive Director of the Commission on Presidential Debates, Janet Brown.

Get more Civics 101 right in your inbox! Sign up for our newsletter!

NOTE: This transcript was generated using an automated transcription service, and may contain typographical errors.

Civics 101

Presidential Debates

[00:00:00] Civics 101 is supported in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

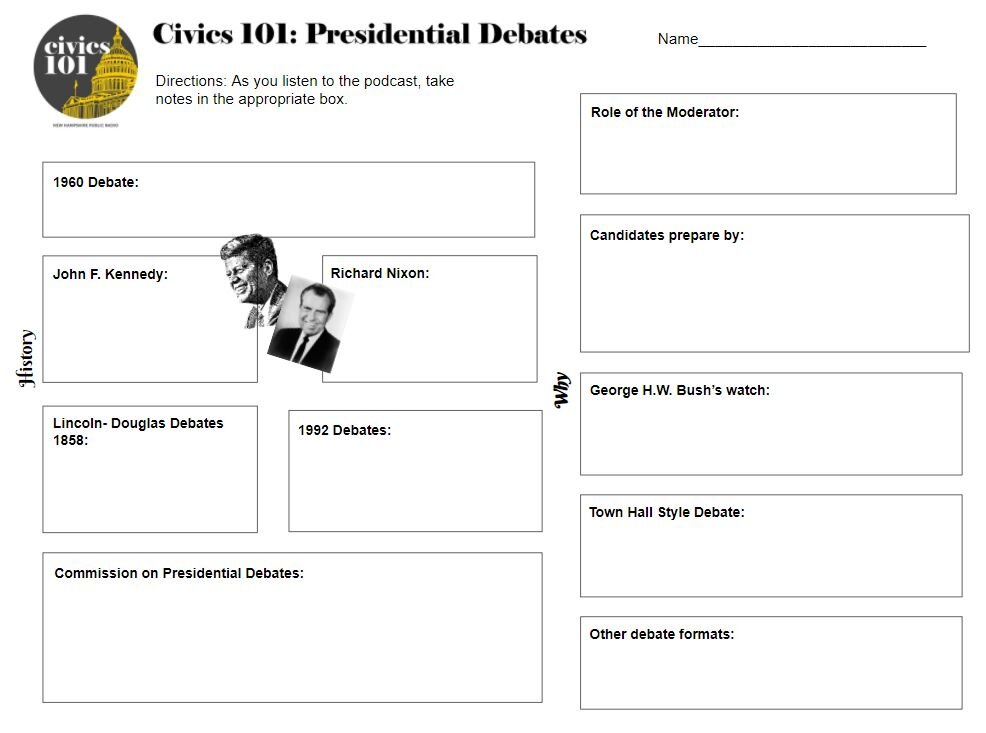

Nick Capodice: [00:00:07] September 26, 1960, nine thirty p.m. The show Peter Gunn had just finished airing on NBC and then 66 million Americans tuned in to watch a revolution in the process for selecting a president.

Howard K. Smith: [00:00:24] Good evening. The television and radio stations of the United States and their affiliated stations are proud to provide facilities for a discussion of issues in the current political campaign by the two major candidates for the presidency. The candidates need no introduction.

Howard K. Smith: [00:00:41] The Republican candidate, Vice President Richard M. Nixon,

[00:00:44] Vote for Nixon and Lodge November eight.

Howard K. Smith: [00:00:46] And the Democratic candidate, Senator John F. Kennedy. According to rules...

Nick Capodice: [00:00:57] I'm Nick Capodice

Hannah McCarthy: [00:00:58] I'm Hannah McCarthy.

Nick Capodice: [00:00:59] And this [00:01:00] is one Civics 101 one, the podcast refresher course on the basics of how our democracy works. And today we're talking about the relatively recent tradition of presidential debates. When did they start? Who decides how they're run? Why do we do them? And what we should be looking for when we watch them? Hannah what is your first debate memory?

Hannah McCarthy: [00:01:19] I would say it's more like an entire season of debates. It was during the Obama McCain election of 2008. And I I knew that I would be turning 18 a couple of days after the election. So I watched these debates with a great deal of pain in my heart because I knew I wouldn't actually be allowed to vote in that election.

Nick Capodice: [00:01:41] I think I saw Saturday Night Live parodies of the debates before I saw the real ones.

Dana Carvey as George HW Bush: [00:01:45] A thousand points of light. Stay the course.

Nick Capodice: [00:01:51] I think my first visceral staying up late, watching the debate memory is October of 1992 between actually, I should say among, George [00:02:00] H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton and Ross Perot.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:02:03] Oh, that's right. That is the first and so far only three candidate presidential debate. That's so cool. You opened with a clip from the 1960 debate between Nixon and Kennedy, which I know was the first televised debate. But it's certainly not the first debate, is it?

Nick Capodice: [00:02:25] Well, here's Alan Schroeder, he's professor emeritus at Northeastern University and he's the author of several books on presidential debates.

Alan Schroeder: [00:02:33] Well, there were the live debates such as the Lincoln Douglas debates, the senatorial debates of 1858.

Nick Capodice: [00:02:39] 1858. Those debates were for a Senate seat, not for the presidential election. But what's interesting about them is they were published two years later when Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas were the presidential candidates. But until the late 19th century, candidates for president did little personal campaigning. Their supporters did most of the campaigning [00:03:00] and attacking of opponents.

Alan Schroeder: [00:03:01] So pre broadcast, there were debates held in person between candidates. They were these big events where spectators would show up by the hundreds and bring picnic baskets and sort of make an all day activity out of it.

Nick Capodice: [00:03:17] But once broadcasting radio and then television came on the scene, there were more attempts to introduce political debates.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:03:24] What was it in 1960 then that caused this change? Why the debates then?

Alan Schroeder: [00:03:29] They were really a creation of the television networks of that era who wanted to be taken more seriously. You know, they were entertainment media, but not so much information media. So the networks in the late 50s saw an opportunity to legitimize themselves by doing political debates on television. And they got John F. Kennedy on board. And once he was on board, Nixon sort of couldn't get out of it without looking like a coward. And so that's how we got the first debates [00:04:00] in 1960.

Nick Capodice: [00:04:01] So Americans who listened to that first debate on the radio were pretty split on a winner. But television viewers enormously favored Kennedy.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:04:10] Why? What happened?

Alan Schroeder: [00:04:11] Nixon had been hospitalized before the first debate and had only recently been released. So he was he had lost a lot of weight. He was pallid. He was lured by the Kennedy people into thinking that John F. Kennedy hadn't used makeup. So by God, he wasn't a use makeup either. And he does look bad. You know, you look at it now and it is you know, he is this scarecrow that the sweating scarecrow that history remembers him has. But you could definitely see how uncomfortable he was and and ill at ease and ill in general.

Nick Capodice: [00:04:49] So in this debate, Nixon and Kennedy were seated when not taking questions and then they would rise to speak behind a shared podium to a panel of news reporters.

Richard Nixon: [00:04:58] I would suggest, Mr. Vanocur, that, [00:05:00] you know, the president that was probably a facetious remark. I would also suggest as far as...

Nick Capodice: [00:05:06] And when Nixon was behind the podium, you could sort of see him bending his knee in discomfort as he answered questions. Now, Kennedy Kennedy had prepared for this debate. He had studied camera angles. He'd read a lot about TV. He wore makeup.

John F. Kennedy: [00:05:21] I come out of the Democratic Party, which in this century has produced Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman and which supported and sustain these programs.

Nick Capodice: [00:05:30] But Nixon treated this just like another campaign event and refused to wear makeup.

Alan Schroeder: [00:05:35] Nixon himself went on what he called a milkshake diet, where he just started pounding the calories and in a hope of gaining weight again and did look better in the later debates. He also learned the hard way to use makeup.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:05:49] I feel like there's so much more to lose in a debate than there is to gain, like a single gaffe, a single mistake, or even what [00:06:00] you look like can affect your electability.

Nick Capodice: [00:06:03] Yeah, maybe this is why after 1960, there were no presidential debates until 1976.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:06:10] Ok, this brings me to the question of who decides how these things are going to go. Like, are they seated or are they standing? How much time do they get? Who asks the questions? Do the candidates fight with each other behind the scenes and then come up with a mutual solution?

Nick Capodice: [00:06:28] They do not.

Alan Schroeder: [00:06:29] Well, every general election, presidential debates since 1988, it has been sponsored and staged by the Commission on Presidential Debates. And then the candidates can either agree or disagree and they'll try to negotiate a little bit around the margins. But basically, they don't have as much clout. The campaigns don't have as much clout anymore as the debate commission.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:06:52] I didn't know that there was a commission on presidential debates.

Nick Capodice: [00:06:55] I didn't either!

Hannah McCarthy: [00:06:56] What do they do?

Janet Brown: [00:06:57] The Commission on Presidential Debates is [00:07:00] a private, nonprofit, nonpartisan corporation based in Washington, D.C. We were created in 1987 and have been doing the general election, presidential and vice presidential debates ever since 1988. We select the moderator and the moderator selects the questions which are not known to the commission or to the candidates.

Nick Capodice: [00:07:24] This is Janet Brown, the executive director for the Commission on Presidential Debates. I called her a week before the first debate of this election cycle.

Nick Capodice: [00:07:32] How are you, Janet?

Janet Brown: [00:07:34] I'm insane. Thank you for asking.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:07:36] How many debates has she run?

Janet Brown: [00:07:38] 30 debates,

Hannah McCarthy: [00:07:39] 30?

Nick Capodice: [00:07:40] 30! The rules that the commission sets are public knowledge, like the format, who the moderator is, the dates. But there are non-public agreements as well. It's not all out in the open. In 2012, a Time reporter published Obama and Romney's memorandum of understanding. That's a document that's the secret [00:08:00] rules for a debate. And that included no direct questions from one candidate to the other, no requests for a show of hands, no call outs to any non-family member of the audience, and an agreed upon comfortable temperature. To be clear, the commission manages presidential and vice presidential debates, not the primary debates. Those are run by the party. And as such, they can get a little wacky.

Rand Paul: [00:08:23] I don't trust President Obama with our records. I know you gave him a big hug and if you want to give him a big hug again.

Ronald Reagan: [00:08:23] I am paying for this microphone.

Nick Capodice: [00:08:39] For presidential debates, the commission adopted the journalist panel format that we heard about from the 1960 debate. That's a format that continued in every debate from 1976 on.

Janet Brown: [00:08:49] But it became clear that if you could reduce the number of other participants on the stage and focus more time and attention on the candidates, that's what serves [00:09:00] the public best. So starting in 1992, we experimented with having at least part of one debate that was run by a single moderator.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:09:10] I'm curious about the town hall format of debates where the audience is a bunch of uncommitted voters and they're speaking directly to the candidates. When did we start doing that?

Janet Brown: [00:09:22] Town hall format actually goes back to 92. It was introduced that year and has proven very popular with the public for one primary reason. People identify with the citizens who have been selected to ask questions of the candidates. As you can well imagine, it changes the dynamic if a candidate is answering a question from a citizen as opposed to a journalist.

Anderson Cooper: [00:09:46] One more question from Ken Bone about energy policy. Ken?

Ken Bone: [00:09:50] What steps will your energy policy take to meet our energy needs while at the same time remaining environmentally friendly and minimizing job loss for fossil power [00:10:00] plant workers?

Janet Brown: [00:10:01] And the nature of those conversations is is quite different than it is when you have a journalist who is conducting the whole debate and and asking the questions. It's a particular privilege to work on those because needless to say, those citizens don't do television on a daily basis. This is this is a a very unusual thing. They come to it with such seriousness and sense of purpose on behalf of their fellow citizens. And that's that's a particularly meaningful one to be a part of.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:10:36] How do the candidates even prepare for these?

Nick Capodice: [00:10:38] They each hire someone to be their sparring partner. It's a crucial role in preparing for debates. Their sparring partner is usually a savvy politician who impersonates their opponent like not their accent or clothing or anything, but their persona, their ideas, the way they might phrase questions and answers. And they do mock debates for days on end.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:10:58] So Janet told us that the [00:11:00] candidates don't know the questions that they're going to be asked. But when they learn who the moderator is going to be, do they prepare based on who that person is?

Nick Capodice: [00:11:11] Yeah, they do. Here's a clip of former President George H.W. Bush talking to journalist Jim Lehrer about his opinion on debates.

George HW Bush: [00:11:18] Ugly. I don't like em,

Jim Lehrer: [00:11:21] Why not?

George HW Bush: [00:11:22] Well, partially, I wasn't to good at them. Secondly, there's some of it's contrived show business. He promised to get the answers ahead of time. Now, this guy, you got Bernie Shaw on the panel, and here's what he's probably going to ask you. You got Lesley Stahl over here and she's known to go for this and that. And you can be sure I remember what Leslie's is going to ask...

Nick Capodice: [00:11:43] And as we learned with Nixon in 1960, the visuals of a debate can matter as much as what is actually said. Alan told me one of the most telling moments in debate history involved the first George Bush glancing down at his watch during a town hall debate, giving the impression to the studio audience and [00:12:00] the audience at home that he had no interest in being there now.

George HW Bush: [00:12:03] Was I glad when the damn thing was over? Yeah, and maybe that's why I was looking at it. Only 10 more minutes of this crap.

Nick Capodice: [00:12:10] That was the town hall debate where a member of the audience asked Bush this question.

[00:12:14] Yes. How has the national debt personally affected each of your lives?

Nick Capodice: [00:12:20] And Bush actually said, I don't get it. And he stayed behind his podium and he honestly did not answer the question.

Alan Schroeder: [00:12:26] And then Bill Clinton comes in right after him and walks to the edge of the stage and directly engages the woman and asks her about her life and empathizes, as only Bill Clinton could do.

[00:12:38] How has it affected you again? You know, people who lost their... Their home. Well, I've been governor of a small state for 12 years. I'll tell you how it's affected me every year. Congress and the president...

Alan Schroeder: [00:12:54] And so, you know, it was it was a telling moment that I think matters, even though it's [00:13:00] trivial in a way, it matters because presidential campaigns strive so hard to control everything that goes out to the public. And so when something busts through the veneer like that, it's, I think, our job as voters to pay attention.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:13:18] You've got the moderated debate. You've got the town hall style debate. Are there any plans for like any other kind of debate format in the future?

Nick Capodice: [00:13:27] Yeah, Janet said there were some ideas boppin around.

Janet Brown: [00:13:28] But if you look back at different debates, there are ones that stand out. And as it happens in Massachusetts and senatorial and gubernatorial races from some years ago, where essentially the moderator served almost as a timekeeper and the candidates were willing to do debates that that essentially were conversations between the candidates.

Janet Brown: [00:13:55] From our work, it's clear that the public wants the maximum [00:14:00] amount of attention and time focused on the candidates. That's who they're trying to learn about. So if we can continue to work toward having the candidates with minimal intrusion, interference by the moderator, that obviously is what the public really finds very, very valuable.

Nick Capodice: [00:14:20] And the commission is responsive and flexible to these debates as they happen. After the first debate in this cycle,

Chris Wallace: [00:14:28] Your campaign agreed that both sides would get two minute answers uninterrupted. Well, your side agreed to it. And why don't you observe what your campaign agreed to...

Nick Capodice: [00:14:43] They made a public statement that they would revisit the format and the rules and a source close to the commission said they were considering cutting mics if the candidates kept interrupting each other.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:14:53] I will say it did recently read that people tuning in to the Trump [00:15:00] Biden debate, the most recent one, 84 percent, said that the debate wasn't going to change their mind either way. So what is the point of a debate if not to change minds?

Alan Schroeder: [00:15:15] I think debates are very important, even if they don't really decide the election, because there's not much during the campaign that belongs to the people, to the voters. But debates do. The journalists have to step aside. The candidates have to respond spontaneously and in real time. And we just don't get that many peeks behind the curtain. And so when one is offered to us, I think we have to pay attention as far as what to keep an eye on during the debate. One of the things that always fascinates me is how do the candidates treat each other? You know, what are they doing when the other person is speaking? What are their facial [00:16:00] expressions toward the other person? And I think you can kind of get some insight into them as human beings just based on that that very little point. How do we treat other people?

Janet Brown: [00:16:13] At the end of the day, they are individual human beings and they're running the gauntlet of a very public and rough and tumble campaign or service. And you are constantly reminded of the poignancy that these are people and that their decisions will involve those closest to them and change their lives.

Howard K. Smith: [00:16:36] I've been asked by the candidates to thank the American networks and the affiliated stations for providing time and facilities for this joint appearance. Other debates in the series will be announced later and will be on different subjects. This is Howard K. Smith. Good night from Chicago.

Nick Capodice: [00:17:02] All [00:17:00] right, that's debate.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:17:03] No, it isn't.

Nick Capodice: [00:17:04] Yes, it is.

Nick Capodice: [00:17:06] Today's episode was produced by me Nick Capodice with you Hannah McCarthy. Thank you.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:17:10] Jacqui Fulton knew Jack Kennedy. Jack Kennedy was a close personal friend of Jacqui's. And Senator, you're no Jacqui's Jack,

Nick Capodice: [00:17:17] Erika Janik is our executive producer and she paid for this microphone.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:17:20] Music in this episode by Chad Crouch, Dyala, Scott Holmes and that composer with the beats so nice and crispy, Chris Zabriskie.

Nick Capodice: [00:17:27] You like political ephemera and deeper dives into these topics. Don't you? Please join our biweekly newsletter, Extra Credit. It's snappy. It's fun. It's at civics101podcast.org.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:17:38] Civics 101 is supported in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and is a production of NHPR, New Hampshire Public Radio.

Nick Capodice: [00:17:50] Oh, come on, do you think I'm not going to put this in here, the greatest debate zinger of all time, we referenced it in the episode, but [00:18:00] you just got to hear it. 1988 vice presidential debate between Dan Quayle and Lloyd Bentsen.

Dan Quayle: [00:18:06] I have as much experience in the Congress as Jack Kennedy did when he sought the presidency. I will be prepared to deal with the people and the Bush administration, that unfortunate event, whatever occur.

[00:18:21] Senator Bentsen?

Lloyd Bentsen: [00:18:24] Senator, I served with Jack Kennedy. I knew Jack Kennedy. Jack Kennedy was a friend of mine. Senator, you're no Jack Kennedy.