The Supreme Court, considered by some to be the most powerful branch, had humble beginnings. How did it stop being, in the words of Alexander Hamilton, "next to nothing?" Do politics affect the court's decisions? And how do cases even get there?

This episode features Larry Robbins, lawyer and eighteen-time advocate in the Supreme Court, and Kathryn DePalo, professor at Florida International University and past president of the Florida Political Science Association.

Episode Segments

TRANSCRIPT

NOTE: This transcript was generated using an automated transcription service, and may contain typographical errors.

Civics 101 –

Starter Kit: Judicial Branch

Adia Samba-Quee [00:00:00] Civics 101 is supported in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

[00:00:10] This Lieutenant White came and showed a piece of paper. And, Mrs. Mapp demanded to see the paper, to read it, see what it was.

[00:00:20] The first plaintiff was Jane Roe, unmarried pregnant girl who had sought an abortion in the state of Texas.

[00:00:27] We can't order you to salute the flag. We can't order you to do all these obeisances around the flag. Can we order you not to do something, to show something about the flag?

[00:00:37] I see that my white light is on, so if there are no further questions I would save my further time for rebuttal.

[00:00:42] Thank you, Ms. Phelan, you have further time. We'll hear now from you Mr. Robbins

Nick Capodice [00:00:49] Do you remember this moment?

Larry Robbins: [00:00:51] Yeah.

Larry Robbins in 1986: [00:00:52] Mr. Chief Justice. And may it please the court. I'd like to begin my remarks by addressing the questions regarding deception...

Larry Robbins: [00:01:02] So is that that's actually from must be from Colorado against Spring. Yeah. I you know, I didn't realize that that one was recorded. I don't know that I've ever heard it.

Nick Capodice: [00:01:13] This is Larry Robbins. He runs a private law practice now, but for years he worked in the office of the solicitor general. That's the office responsible for arguing on behalf of the United States in the Supreme Court. I called him up because I wanted to know what it's like to stand there alone under the eyes of Rehnquist, O'Connor, Ginsburg, Marshall.

Larry Robbins: [00:01:35] What's remarkable, though, it was to me anyway, the first time I stood up at the lectern is how close to you the justices are. I always I guess I always analogize it to sitting in a living room with nine very smart people who have thought about the same problem that you have and want to ask you some questions about it. And your job is to answer them. That's how it felt to me. And I've done it 18 times and it always feels like that.

Nick Capodice: [00:02:10] It's the judicial branch today on Civics 101. I'm Nick Capodice.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:02:13] And I'm Hannah McCarthy.

Nick Capodice: [00:02:14] And while I studied acting in college, on a whim I took this one class on the First Amendment. Where the only texts we were assigned were Supreme Court opinions. And thereafter, I took every single course that professor taught. And I just carried a torch for the third branch ever since. Hannah, what would you say if I told you that the judicial branch is, quote, beyond comparison? The weakest of the three departments of power, that its next to nothing?

Hannah McCarthy: [00:02:42] I'd say you were terribly misinformed.

Nick Capodice: [00:02:44] I know, but that was a direct quote from Federalist 78 by Alexander Hamilton, because initially the Supreme Court did not have that much power. But there was a night. Then everything changed.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:02:59] Lay it on me.

Nick Capodice: [00:03:01] You're going to love it. I'm standing up. The presidential election of eighteen hundred, the two major political parties, the Federalists and the Democratic Republicans. Thomas Jefferson, the Democratic Republican beats the incumbent Federalist John Adams, 76 electoral votes to 65.

Nick Capodice: [00:03:23] And Adams becomes what they call a lame duck president. He's just sitting around until Jefferson is sworn in on March 4th. It's like spring of your senior year, right. But Adams and his federalist Congress, they don't just sit there. They go to work in the lame duck session. They pass this law called the Judiciary Act of 1801. And it's a new version of the Judiciary Act of 1789. I promise this is important, which creates a ton of new courts in the United States. And Adams uses his executive power of appointment and just packs those courts full of Federalist judges. The very night before Jefferson comes to the White House, they have appointed 16 circuit judges and 42 justices of the peace. These were called the midnight judges. Got all their albums. So you get a judge commission and you get a judge commission. Adams's Secretary of State John Marshall, he's just running around frantically trying to give out these judgeships and some of them didn't get delivered.

Nick Capodice: [00:04:20] Tom Jefferson is sworn in, and one story goes that he sees all of these judge commissions on the table and says, oh, no, you don't. And he maybe throws them all in a fire.

Nick Capodice: [00:04:33] One of those potential judges, William Marbury, sitting by the phone with a ham sandwich waiting for his commission to arrive. He goes to the Supreme Court to sue Jefferson's new secretary of state, James Madison. He says, hey, I was promised this judgeship. I didn't get it. He's furious. And the chief justice of the Supreme Court is John Marshall.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:04:54] Hold on one second. John Marshall was Adam's secretary of state. The guy delivering all those commissions.

Nick Capodice: [00:05:01] Yes. And the Chief Justice, John Adams, was like, all right, my term's ending. Can you just do both jobs until Jefferson comes to office? So William Marbury, he thinks he's got this one in the bag. He's asking the court to issue what's called a writ of mandamus, which is where the court orders the executive branch to do something to give him that judgeship. And Justice Marshall, stunning everyone, says, I'm sorry, Bill, I can't do that. Because that 1789 Judiciary Act was unconstitutional. And we the Supreme Court, we have a job to do. And it is not to make people do things. Our job is to say whether or not something is constitutional. That case, Marbury vs. Madison, establishes judicial review.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:05:53] All right, I was wondering where you're going with that story. But this is pretty significant. A branch giving itself a major power, maybe the most major power.

Nick Capodice: [00:06:03] Yeah. And apparently a kind of flew under the radar at the time.

Kathryn DePalo: [00:06:06] Now, a lot of people make a big deal about Marbury versus Madison today.

Nick Capodice: [00:06:10] This is Catherine DePalo. She's a political science professor at Florida International University.

Kathryn DePalo: [00:06:15] But at the time, it kind of came and went with a whimper. Right. Because nobody really said, oh, gosh, now this gives the U.S. Supreme Court all this power of judicial review to declare something unconstitutional. You know, the courts were kind of an afterthought. They weren't really thought as as, you know, as equal as Congress and the presidency, at least in people's minds. You know, in the Capitol building, they met in the basement.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:06:39] The Supreme Court used to meet in a basement.

Nick Capodice: [00:06:41] Yes. Catherine told me that after Marbury versus Madison, the court didn't rule something unconstitutional again until 1857, the infamous Dred Scott decision, where the court ruled that an enslaved person was not a citizen and had no rights. The Supreme Court didn't really kick into its modern, more powerful iteration until the 20th century.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:07:01] So if they weren't declaring laws constitutional or not, what were they doing? What are their constitutional powers?

Nick Capodice: [00:07:09] The Constitution establishes the Supreme Court and it lays out that justices are appointed by the president with the Senate's approval. But it doesn't say how many justices there should be, though it does specify a chief justice. Originally, there weren't nine justices. There were five in the eighteen hundreds. And the number increased over the years by acts of Congress, cementing it at nine justices in 1869. It's left to the Congress to decide how the lower courts would be set up.

Kathryn DePalo: [00:07:36] There are some specific things that the U.S. Supreme Court is tasked with doing.

Nick Capodice: [00:07:40] One of those is settling disputes between the states.

Kathryn DePalo: [00:07:43] So if New New York wants to sue New Jersey over a particular matter, the Supreme Court is there to settle some of those disputes. Other things, you know, involve cases involving ambassadors and and these particular things. But it's so vague. And really, the Supreme Court is not used as a trial court much anymore.

Nick Capodice: [00:08:03] The Supreme Court is what's called an appellate court, which means that it hears appeals. It's not like a trial court. There's no jury. So someone loses a case in another court. They think it's not fair. They can appeal it up the chain.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:08:15] Appellate appeal.

Nick Capodice: [00:08:18] Yeah.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:08:19] How do cases get to that level where they're ruled upon by the highest court in the land?

Nick Capodice: [00:08:24] Here's Larry Robbins again.

Larry Robbins: [00:08:25] The Supreme Court, to my knowledge, is the only federal court and one of the few kinds of appellate courts that you have no inherent right to be heard in front of. You have to ask their permission and they grant it only very rarely.

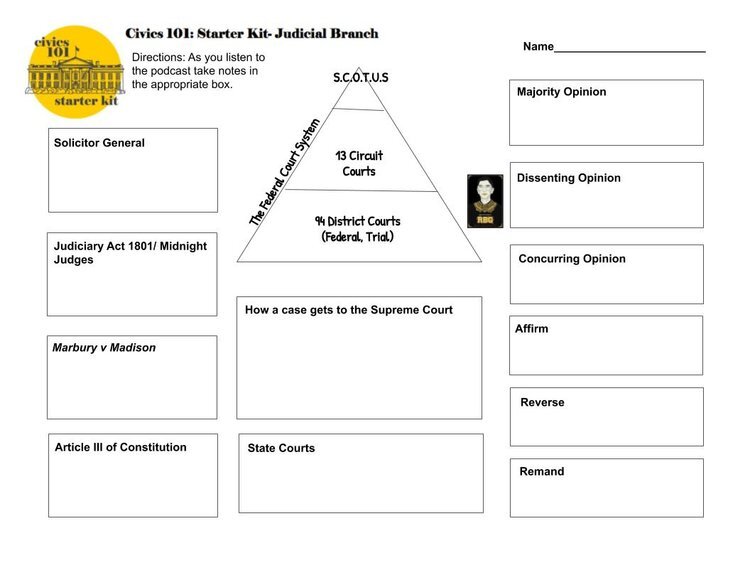

Nick Capodice: [00:08:43] It's a long process. And as Larry says, it's super rare, but it helps illustrate the entire federal court system instead of just those nine justices at the top. First off, Hannah, most trials in the U.S. are gonna be in your state court. You stole a car, you got a divorce, you jumped a subway turnstile, state court. Federal courts are for when your case deals with the constitutionality of a law or if the United States is a party in the case or if you broke a federal law. Currently, there are 94 federal trial courts and those are divvied up into 13 circuits, kind of like the NCAA

Hannah McCarthy: [00:09:19] Right. So it's like the West Coast is one circuit.

Nick Capodice: [00:09:22] Right they're the 9th Circuit.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:09:22] And what circuit are we in?

Nick Capodice: [00:09:24] We in New Hampshire are part of the first circuit, which also includes Maine, Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Puerto Rico, interestingly.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:09:31] Yeah.

Nick Capodice: [00:09:32] So if you lose a case in one of those 94 federal courts, you can appeal it to your circuit court. And a court of appeals trial has no jury. Its lawyers arguing in front of a panel of three judges.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:09:44] And if you lose that appeal, what happens then?

Nick Capodice: [00:09:46] We are on the road to getting your case into the Supreme Court.

Larry Robbins: [00:09:49] A case begins with an application to the Supreme Court to hear the case. This has a very fancy name with some with a Latin component because lawyers like to sound as obscure as possible. So it's called a petition for a writ of certiorari,.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:10:08] Petition for a writ of certiorari.

Larry Robbins: [00:10:11] What's called a cert petition for short. And what a cert petition does is it says to the Supreme Court, you should hear my case.

Nick Capodice: [00:10:20] And like Larry said, the Supreme Court does not have to do it.

Larry Robbins: [00:10:23] The vast, vast majority bordering on 98 or 99 percent are denied.

Nick Capodice: [00:10:30] If four of the nine Supreme Court justices agree to hear a case, then it will get a hearing in the Supreme Court. And only about 100 of the nearly 7000 cert petitions are granted.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:10:42] Are there any types of cases that tend to be granted more than others?

Nick Capodice: [00:10:46] Yes. And Larry had some tips on that.

Larry Robbins: [00:10:48] The most important thing you can say to get the Supreme Court interested in granting your case is that there is a question of federal law because the Supreme Court is there to decide federal questions, not state law questions, but federal questions, either questions about federal statutes or the United States Constitution. And what you want to tell the court is, look, there is a important federal question that the courts of appeals, the lower federal courts disagree about.

Nick Capodice: [00:11:22] There's hundreds of publications and Web sites out there that track these circuit splits, where two circuit courts are divided on an issue.

Larry Robbins: [00:11:29] Even better, if you can say there are three circuits on one side of the question and four on the other side of the question. So that, you know, the issue has been widely considered. The question has percolated in the courts of appeals, if you will. That's a Supreme Court lawyer's term of art.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:11:54] I have a question.

Nick Capodice: [00:11:55] Yeah, go ahead.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:11:56] So the Supreme Court, a seemingly passive political body, does have some political power because they can decide what cases they want to hear or not. And presidents campaign on what kind of Supreme Court justice they'll appoint. But if a justice wanted to pass a controversial ruling, they can't bring it up themselves, can they?

Nick Capodice: [00:12:15] No, they cannot.

Kathryn DePalo: [00:12:16] We talk a lot about how much power the court has. And I think some of the power of the court, particularly the U.S. Supreme Court, has significant power in shaping a policy agenda. You know, if there is a ruling that they make, all of a sudden everybody's talking about it. And you point to Roe v. Wade in 1973 and we're still talking about that. It separates our political parties and our system. That's that's power that's setting an agenda. However, the power of the courts is really limited because the Supreme Court, you know, can't be watching, you know, TV and say, what the heck's going on? Let's make a ruling. They have to wait for the process to begin.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:12:50] Ok. So that's how a case gets into the Supreme Court. What happens once you're in there?

Nick Capodice: [00:12:55] Have you actually have you been to the Supreme Court chamber?

Hannah McCarthy: [00:12:57] I have not. Have you?

Nick Capodice: [00:12:58] Not since seventh grade. Anyone can visit it and witness the oral arguments. It's sort of this hallowed date; The first Monday in October until about mid-April, the court hears arguments and they make decisions. And when they're in recess, they choose their next session's cases and they prepare for those. People will wait in line sometimes from 5:00 a.m. like a rock concert to get a seat.

Larry Robbins: [00:13:19] In the years that I was in the SD office, The Supreme Court heard many more cases than they do these days. In those years, which were 1986 to 1990, there were typically four arguments every day that almost I think never happens anymore. The court doesn't grant as many cases as it used to.

Nick Capodice: [00:13:40] After the argument, usually the same week, they meet privately and they vote. The senior justice in the majority decides which justice, with a lot of help from their clerks, is going to write the opinion. Drafts circulate, edits are made. These opinions take time.

Kathryn DePalo: [00:13:56] Mostly most the time there is a majority opinion, whether it's 5 to 4 or 9 to 0. They they often on the court want to not have closely divided opinions because that doesn't look good for the court. Certainly going forward, that might not stand if you have a change, a composition of the court and then justices certainly that disagree can write dissenting opinions. And Ruth Bader Ginsburg, I think, has written some of the more interesting ones, expressing her legal rationale for why she thinks the majority got it wrong and what she thinks would be the proper course. Some write concurring opinions, meaning they're part of the majority, they agree with the majority, but they may disagree on some other point or they may expand on some issues that the court did not agree to, did not address. So they'll talk about those particular things as well.

Nick Capodice: [00:14:47] And while the opinion and dissent lay out the legal reasoning for a decision, the ruling is usually one of these three things: affirm, reverse or remand. Affirm is that the finding from the lower court is upheld. So the petitioner was unsuccessful in their appeal. Reverse is the opposite where the lower court's ruling was in error and it's overturned and the petitioner wins the day. And finally, remand is where the case is sent back to the lower court for a retrial with any irregularities corrected.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:15:20] One thing I'm curious about goes back to something that Kathryn said earlier about a court furthering a political agenda. Does the party of the president who appointed them have influence on their decisions?

Larry Robbins: [00:15:35] Look, I think. I think it's possible to overstate the significance of who appointed a particular judge or justice. I'm close to agreement with my old friend, who is now the Chief Justice, John Roberts, who I think famously responded to one of the present President Trump's tirades about Obama judges by saying there are no Obama judges, there are no Bush judges, there are just judges trying to do their level best. But I don't think, you know, anybody should be so naive as to imagine that political ideology has no impact. It certainly does.

Nick Capodice: [00:16:22] Larry told me one thing about how political ideology affects the law, and it's something I'd never considered before. It's that right now such a high percentage of judges in the lower courts are conservative. And that means there's less disagreement between the circuits on rulings, which in turn means there are fewer cases presented to the Supreme Court for writs of certiorari. And this goes back to what Larry said, that the Supreme Court every year is hearing fewer and fewer cases.

Hannah McCarthy: [00:16:47] Last thing, these justices are appointed for life. They often outlive the presidents who appoint them. And they're not Constitution-interpreting blank vessels. They have strong opinions. Right. So how do they interact with each other when they're off the bench?

Nick Capodice: [00:17:02] Larry refused smartly, I believe, to go on the record about that. But Kathryn had a specific example that I thought was just lovely.

Kathryn DePalo: [00:17:11] The late Justice Scalia of probably one of the most conservative jurists we've had on the U.S. Supreme Court was best friends with Ruth Bader Ginsburg, one of the more liberal justices we've seen in the history of the court. And they had this love of opera together and they would would go see operas and they would have dinner with the spouses. And were really the best of friends. And, you know, you can't find two really more opposite people. A lot of the justices have said, you know, it's not like in Congress where, you know, I'm going to yell at you for having your position. I respect your position. I may not agree with your position, but you have the right to say that and we move on. So I think the fact that they're all trained lawyers and have gone through the advocacy processes in their careers and understand you're going to win some, you're going to lose some, I think is particularly important. And I think that's how the court continues to operate.

CREDITS:

Today’s episode was produced by me Nick Capodice and you Hannah McCarthy, with help from Samantha Searles.

Erika Janik is our Executive Producer and burner of judicial commissions, Maureen McMurray only judges things at midnight

Music in this episode by Tonstartssbandht, thank you, Edwin, Chris Zabriskie, Doug Maxwell, the Grand Affair, Emily Sprague (I love all her stuff), Yung Kartz, and the MIT Symphony Orchestre

Archival Supreme Court audio comes from Oyez, o-y-e-z-.org, the greatest most wonderful resource from Cornell’s legal information institute

Hey, and I got two people to thank. First off, Keith ‘hip’ Hughes whose video on Marbury vs Madison I watched a hundred times check it out, and second, Professor Michael Brown from Emerson College, the guy responsible for the fact that I shall never forget that article 3 section 2 paragraph 1 says, “The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution”

Civics 101 is made possible in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and is a production of NHPR, New Hampshire Public Radio.